The Medical Essay I’ve Been Afraid to Write and Make Real

But here’s where we are as June comes to an end

The Medical Update. June 26, 2025

People keep asking me what’s going on. So here it is. Here’s the whole damn thing.

How common is my diagnosis?

How common is it to survive to fifty?

I’m tired of coded language. So I’m going to tell you what it is like. STAT1 is not very common, especially in this progressive form that I seem to have.

And how common is it to survive to fifty? Not common, or known, at all. Not like this. Not with this much disease burden.

STAT1 gain-of-function was rare and only identified as a mutation in 1989. So long-term survival isn’t tracked.

Patients never used to make it out of childhood. Now, many will not survive without a successful bone marrow transplant.

Even with today’s newer protocols, I didn’t make it through mine in June 2023. Ten percent don’t make it through, and I, of course, was one in ten. I also think I’m the patient with the best hair and highest IQ, but apparently, that “doesn’t count.”

But honestly, there is no five-year survival rate for someone like me. There’s no study because I am the study.

There’s no one else managing this specific combination of disease: aggressive skin cancer, type 1 diabetes, adrenal failure, gastroparesis, lupus, and a severe primary immune deficiency. There’s no cohort. No group chat. No one to text about these very exacting details.

I’ve written about this disease for years. I’ve hashtagged everything. I started the STAT1 Facebook group. NIH calls me the Stat1 whisperer. (I prefer Baby Whisperer.) But I mostly talk to moms in the group, because this is a pediatric disease. Their kids are the ones at high risk of dying. Me? I’m the one who lived long enough to lose the plot. I’m the one they don’t want their kids to turn into. I’m their biggest fear.

—

When my dermatologist dropped me in favor of oncology and my PET scan returned in June, it lit up everywhere: legs, abdomen, shoulder, and ear. And my liver. That was new. The report said “highly concerning for metastatic disease.”

No one has said the words “stage IV” to me yet.

But the spread matches what would usually be considered stage IV in this kind of cancer. This amount of widespread cancer is considered equivalent to stage IV by the American Skin Cancer Society.

I pieced together most of it myself, like I’ve done most of my medical life.

I’ve always had to translate what they were really saying, catch what they weren’t saying, and find the story hiding between the lines of the chart, especially because almost every single doctor I meet knows nothing about STAT1 GOF.

If the term stage IV scares or surprises you, allow me to be more clear:

This isn’t just a FEW skin cancers.

This is crusting, ulcerating, bleeding cancers falling off my body daily. My cancer means finding pieces of ear cartilage on my pillow every morning.

This is me, a walking, living dermatologic emergency. The skin is your barrier against the world, and mine is highly compromised.

Most people with non-melanoma skin cancer develop four to six lesions over ten years.

I have at least fifteen to twenty active lesions right now. And I’ve already had 4 Mohs surgeries in the past. It just grows in volume and depth and length every day.

The PET scan found cancer where there wasn’t a visible lesion—until I woke up three days later, and there it was.

This puts me in the less-than-0.01% of skin cancer cases for disease burden and distribution.

I would be reading this as a case study, but I’m the case.

So, what’s the plan?

There isn’t a clean one.

There’s a chance I’ll start with Mohs surgery and plastics—the foot first, then the ear.

There’s also a chance I’ll need radiation and immunotherapy first to shrink the tumors. The foot lesion is large and painful.

The immunotherapy they’re considering is Libtayo, a PD-1 inhibitor. It works by lifting the brakes off the immune system, helping T-cells recognize and attack cancer cells. In most people, this can be life-saving. In me, it’s dangerous. My immune system doesn’t follow the rules—it’s broken, deep in the DNA.

I’ve done this before—with ATG, an immune-modulating immunotherapy I received during my bone marrow transplant at Memorial Sloan Kettering. It triggered a severe inflammatory reaction, likely a cytokine storm, that spiraled into near-fatal complications. My body doesn’t love immune system manipulation. The same risks apply here: uncontrolled inflammation, infections I can’t fight, organs that can’t keep up.

But my ear lit up brighter than anything else on the scan. The cancer is eating into the cartilage. It’s already changing the shape of my ear. Surgery will change it more.

The plan?

Mohs, for sure.

Immunotherapy, yes.

Radiation, maybe.

We’ll know the order of the treatment when I see my oncologist on July 8.

Side effects? Fever, fatigue, joint pain, nausea, and life-threatening inflammation.

The real side effect is the one I already have: a body no one knows how to map.

If you’re asking for survival odds? I don’t know. There’s no data for someone like me.

I don’t have the cure. I get to be the example. The guinea pig. The what-not-to-do.

I don’t have exact numbers because they’re evolving each morning I wake up and get out of bed, each morning I stay in bed, each night with a fever, and each night with a margarita.

I’ll be a chapter at the end of this. A clinical chapter, at that.

My story will be told in units of blood and med dosages.

So I will write my own, starting with the journal I got in April 1993, when I was seven years old—the journal that still sits on my bed today.

My friend, the late Lisa Adams, taught me how to make a spreadsheet to track my symptoms. But I lost track of keeping track. Instead, I have phones full of Notes. An Instagram full of hospital stays I don’t even remember.

So no, I don’t have time for a five-year plan. It’s not worth saving money for anything except a vacation.

My five-year plan is to watch Leo hit his first out-of-the-park home run.

I want to hear Adelaide nail her first solo song—whether at a school talent show or maybe even on Broadway.

I want to see Sadie dance all over the country, including Ireland.

Because this isn’t all hospitals and scans and countdowns.

It’s also Leo and I playing video games yesterday.

It’s holding hands while we watched The Sandlot.

It’s trading hits and pitches in our new baseball gloves today, painting bird feeders, and watching them swarm in.

Leo told me the birds were Pop-Pop missing us. And I fully believe him.

It’s watching Rookie of the Year and catching a few innings of the Yankees game. It’s me writing this piece while Leo played with my brother, and while he paid off his Mario Party debt by picking up dog shit 😂.

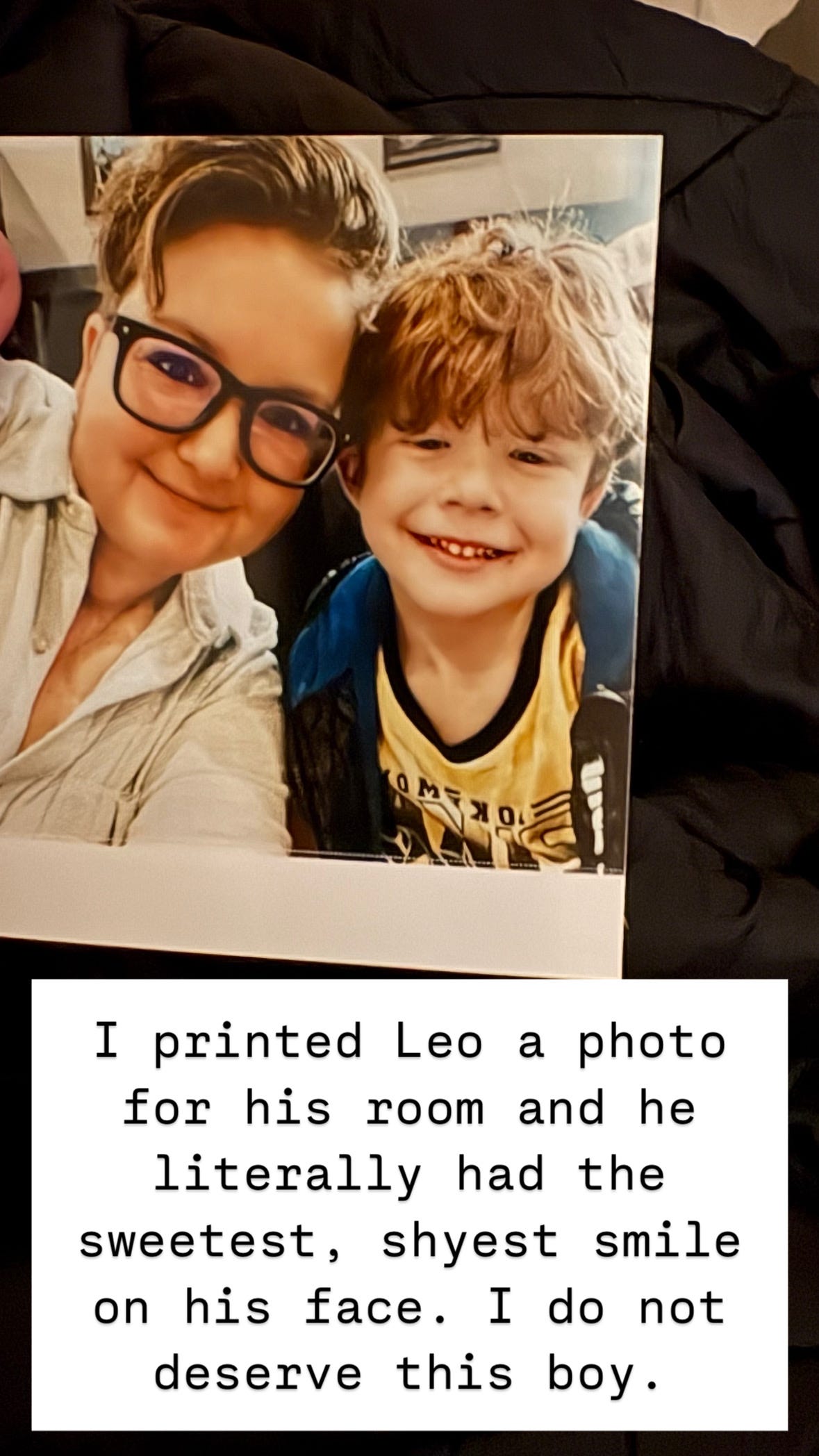

It’s him asking for a photo of us for his room, and me printing it last night when I couldn’t sleep.

That’s the thing: these are the sparks. These are the days I want to burn into his and his sisters’ memories.

Not the hospital wristbands. Not the PET scan reports. This.

Life alongside this devastation will be easing into a new hobby, where I work with my hands.

It’ll be sliding down water slides with Adelaide and becoming temporarily airborne, free of the shackles that have nailed me to a hospital bed for the last thirty-nine years.

There’s no part of me looking forward to exiting this earth.

But if that airborne, dive-off-a-cliff feeling accompanies my exit, I would be okay with that.

Right now, the pain prevents me from paying attention to my life.

And that roadblock is made of my suffering, my exhaustion, my rage.

I don’t save for retirement.

I save for the next trip.

The next walk.

The next spark.

I want to leave them with memories of me that burn bright inside their chest.

I don’t want to leave empty-handed, waiting for me to hold.

I want their hands full of sparks.

Full of memories.

Full of an aunt who never, ever gave up.

And cue the tears. You're already burned into their hearts - and ours - as pure joy, stomach-clencing laughter, and the picture of a great friend. Love you.

XOXO